The Muscular Compassion of “Paper Girl”

Ever since Donald Trump was first elected President, in 2016, a slew of books have attempted to reckon with the growing divide between urban and rural populations in the United States. Few do so as deftly as Beth Macy’s new book, “Paper Girl: A Memoir of Home and Family in a Fractured America.” Throughout her career as a journalist, Macy has covered rural poverty and corporate greed. Her 2014 book, “Factory Man,” followed a Virginia furniture-maker’s fight against Chinese offshoring; in 2018, she published “Dopesick: Dealers, Doctors, and the Drug Company that Addicted America,” an investigation of the opioid crisis that was subsequently adapted into a Hulu series. If “Dopesick” captured the rural discontent that was festering before 2016, then “Paper Girl” might be seen as its spiritual sequel, focussing on how Trump’s Presidency left the nation even more fragmented. This time, Macy gets personal, using her deeply red home town of Urbana, Ohio, as a ground zero for understanding right-wing radicalization. Rather than dismiss her religious sister or her conspiratorial ex-boyfriend, Macy digs deeper, excavating a topsy-turvy world where many people still believe that Trump won the 2020 election. It can be easy to become disillusioned with the other side, to abandon all notions of mutual respect and understanding. It’s much harder, as Macy writes, to “scramble for hope fiercely, the way a farm girl wrestles a muddy sow.”

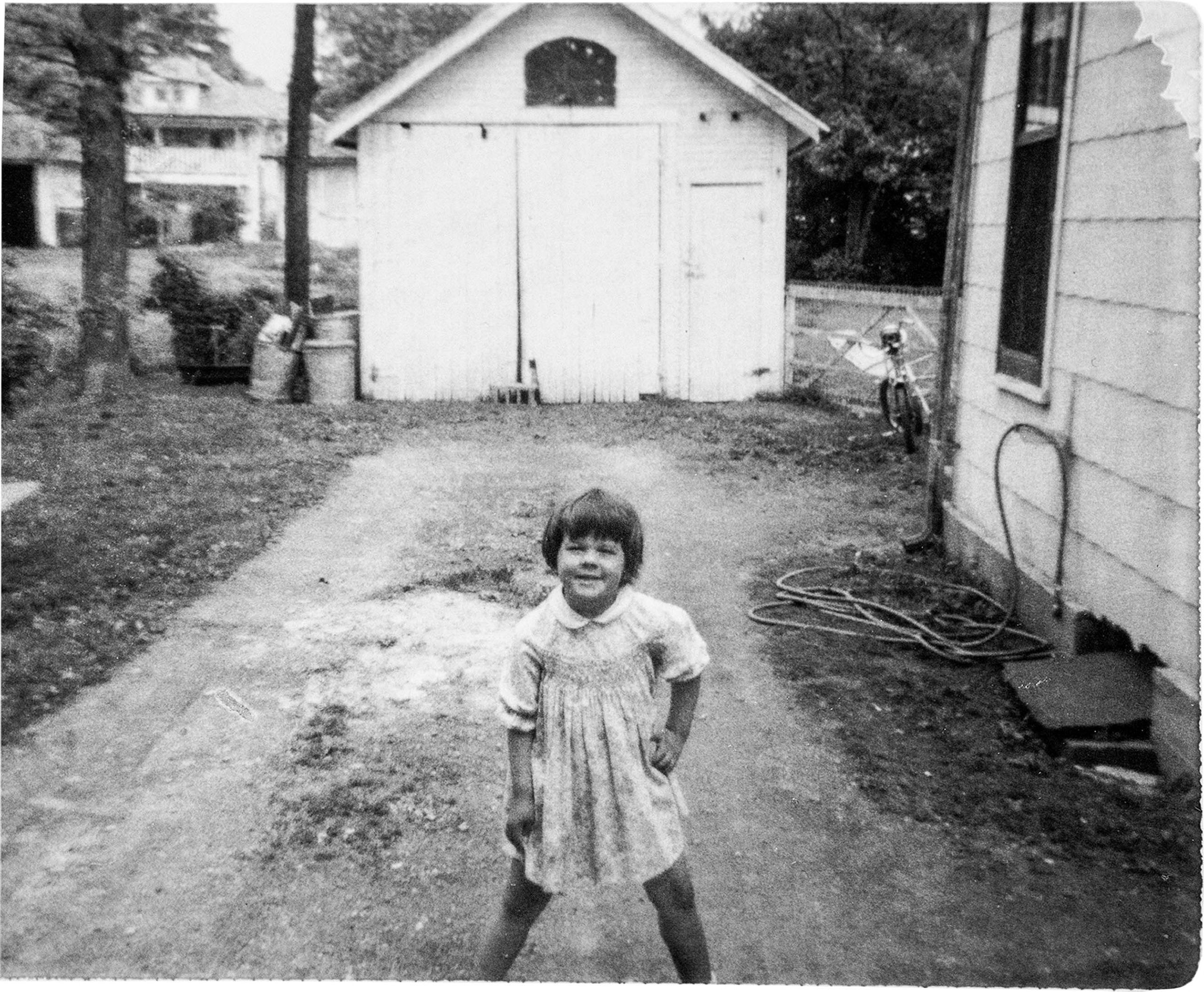

Macy is the paragon of liberal brain drain: she left Urbana in 1982, when she went to college, and subsequently moved to Virginia. Her relationship with her family is fraught, and not just because of her liberal politics; religious animosity, personal grudges, and class resentment all play a part. After “Dopesick” was published, to critical acclaim, Macy became a media darling, further distancing her from her home-town roots. (The Hulu show, which features two lesbians struggling in coal country, didn’t help matters.) But there was also a history of abuse and addiction within Macy’s family, and she struggled to get them to discuss it openly. The author never imagined that she would return to live in Urbana, let alone write a book about it, but she embarked on the project after the 2020 election, deciding to figure out “what happened to my country, my hometown—and my family.”

Once there, Macy encounters a town where nothing is quite as she left it. Urbana always had a conservative bent, but its politics have become a defining feature in the intervening years. Now everyone seems to own a gun and have a far-right sign in their front yard; even her once liberal ex-boyfriend is spouting misinformation about Haitian immigrants. The local newspaper—where Macy was once a paper girl—has been reduced to a glorified pamphlet. Many lives have been ravaged by drug addiction and incarceration. “The more time I spent back in my hometown, the more I recognized the unprecedented forces that were actively turning the community I loved into a poorer, sicker, angrier, and less educated place,” Macy writes.

Although “Paper Girl” is partly centered on Macy’s struggles to reconnect with her family, the star of the book is a young trans man named Silas, whom she befriends. His inclusion could come across as a cynical ploy, a way of measuring social progress in a backward town. But Macy’s interactions with Silas, and his role in the book, feel organic; she does not reduce him to his gender. Silas meets Macy at a crucial point in his life. After scraping by in high school, he’s trying to keep up at college while working as a welder, and he’s looking after his siblings, who have been removed from the care of his drug-addicted mother. Macy worries he may never graduate. She is astounded by the sheer amount of hustling required in Silas’s daily life. She documents the socioeconomic factors working against him—his inability to get financial support for school, the lack of well-paying jobs available, the number of family members battling addiction, and the eternal challenges of getting reliable transportation. But his resilience continually surprises Macy, who suspects she would not have had the same endurance as the new generation. She encounters many children who are hoping to make it big on social-media apps like TikTok—who see fame as their ticket out of a life in which they’re working multiple jobs and will never make enough money to go to a “good” college. For some of these kids, college attendance is actively discouraged by their parents, who fear that if their children do end up leaving, they may never come back. Or, worse: they’ll come back changed. “It’s no longer just whether you can afford college,” one former senator’s aide tells Macy. “It’s the whole ‘If you go to college, you’ll leave home, move to a city, and you’ll turn into a liberal.’ ” Macy cites a statistic: one in five Americans has lost touch with loved ones over their politics. She wonders who is more brittle, less able to reach across the divide, liberals or conservatives?

Macy’s own youth was hardly idyllic, even if she was ultimately able to get a good education and move up to a higher class. She attributes this to a few key factors—a mix of personal and public infrastructure that no longer exists: her supportive and fiercely loyal mother, now deceased; the funding she received from the federal Pell Grant program, now gutted; and robust local journalism, now decimated. Macy acknowledges that she was always a “striver,” but, back then, it was easier to strive. For good students facing economic hardship, the Pell Grant was a godsend. The program began in 1973, but, over the years, it has been kneecapped by politicians, who have argued that it is too much like welfare. College tuition, meanwhile, has only become more expensive. Macy wonders if she could even get a job in local journalism today, given the meagre number of newspapers that are still offering full-time positions. It’s an issue that she’s personally invested in, but the problem has broader ramifications: Macy draws a link between the collapse of local journalism and the rising number of people who take refuge in online conspiracy theories. Even the journalism that remains is often behind a paywall, she notes, contributing to the isolation of communities who need trustworthy news sources the most.

Like Naomi Klein’s “Doppelganger,” which thinks through digital mirror worlds and online radicalization, and Ta-Nehisi Coates’s “The Message,” which examines the role of storytelling in shaping—and distorting—histories of racism, Macy’s book analyzes how the political right has deflected blame and embraced victimhood in the wake of Trump’s rise to power. But Macy doesn’t let the left off the hook, either—she knows that rural communities have good reason to feel aggrieved, and that, too often, Democrats have ignored the important role that class plays in such aggrievement. Inflation is rising, jobs are going overseas, and rents aren’t getting any lower. Downplaying these issues, the way that Democrats did on the campaign trail—or, as Macy puts it, “living in Kamala la-la land”—only exacerbated the preëxisting tensions between rural populations and urban élites. Macy, like Klein and Coates, toggles between personal narrative, history, and reportage to weave together a surprisingly moving account of how politics can rupture the personal. This technique, sometimes referred to as the braided essay, is divisive, with critics arguing that it’s essentially a stylistic crutch: a way for writers to pad otherwise weak or flimsy work with something that feels more substantive. Yet Macy demonstrates the genre’s elastic power, collating large amounts of information into a cogent and thrilling story—a history lesson made more easily digestible as memoir, rather than a memoir with forced-in historical passages. Macy is a surprisingly empathetic narrator, seeking to find common ground with QAnon conspiracists and Second Amendment fundamentalists, without ever minimizing her own beliefs. She has long, in-depth discussions with her detractors, all the while insisting on the humanity of trans kids and migrants. Her conversations are heated, but never stilted; she refuses to foreclose the possibility of redemption, always searching for some element of compatibility. She even admonishes liberals who say the New York Times was too soft on Trump. “Come on,” she moans.

As Macy gets to know the various inhabitants of Urbana, she stumbles on a series of individuals who have remained committed to a community that refuses to fully accept them. In addition to Silas, she meets Brooke Perry, a truancy officer who isn’t afraid to get up close and personal with students who are skipping school, and spends time with Mark Evans, an amateur historian who wants to teach the town about its role in the Underground Railroad. All three struggle to come to terms with the way the other residents of Urbana treat them. At one point, Macy realizes that she doesn’t even think of Silas as trans—although while applying for jobs, he must consider the possibility of being outed when handing over his mismatched identification for payroll enrollment. (Not every trans person is able to get I.D.s that match their gender identity, especially in red states.) Macy’s own family, meanwhile, struggles to accept both Macy’s gay son and her nonbinary child.

Some of this homophobia stems from religious fervor, but the research peppered throughout “Paper Girl” also suggests that globalization and austere economic policies are some of the key contributors to political polarization. Simmering aggressions have to go somewhere, and minorities often become the targets; they are easy scapegoats, simply for being an “other.” The “others” are taking jobs, seducing daughters, and sowing discontent. The majority can then take on the posture of a victim, fearing for their physical and economic safety. This is the basic recipe for civil war—one youth-center volunteer even jokes to Macy about America going the way of “The Hunger Games.”

Does knowing this, however, lead to actual understanding? Despite all her research—and even after seeking professional advice about how to speak with her sister—Macy does not have much success reaching across the aisle to her family. She wonders how Silas can stand it. He marches on; a metalhead, he gets a System of a Down tattoo. He even tries to help Macy reconcile with her intolerant sister. “Here he was, counseling me,” she writes. “And it helped.” The conversations Macy has in this book—both with her family and others in MAGA world—are fascinating, but never entirely fruitful; she does not close the growing divide, nor does she even narrow it, despite providing a stirring and muscular vision of compassion. Rather than blame the people of Urbana for their scorn, she places the blame on a demagogue who has dialled up strife and discord in the country for his own greedy ends. There is some naïveté, perhaps even some wishful thinking, in Macy suggesting that most of this is Trump’s fault, as she does at the end of her book. Her more compelling argument is that the one-per-centers are squeezing out the middle class. By excluding low-wage families from college education and other opportunities, they’re removing “the ladder of upward mobility,” as she writes. “They took away the thing that soothes misery and distress; they took away their hope.”

Early on in “Paper Girl,” Macy declares the book a love story—or at least, her version of one. The book reads more like a letter left behind to the next generation, one with many ideas and few real solutions. Extending grace is easier said than done. But Macy offers some advice: “The answer to our epidemic of loneliness isn’t to seek solace in conspiracy theories; it’s to participate in real life with other human beings, including those we don’t know.” It’s not a ladder, but it might be a bridge. ♦